Image via Wikipedia

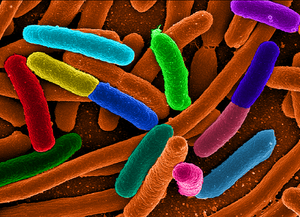

Image via WikipediaAs of June 15, the number of people who were ill due to the outbreak of a new

E. coli strain in Europe had reached 3,244, according to the Associated Press (AP). Most of the reports have been in Germany, and 784 of the total had developed a serious complication that could lead to kidney failure. AP reported that 37 people have died in Germany, and one person died in Sweden.

The German government has said that it could be a while before the outbreak could be tracked to its ultimate source. Critics have lost no time carping about the way the crisis has been handled.

While the epidemiology has been cumbersome, the genomic

sequencing that characterized the pathogen wasn’t. It took all of three days for teams at the

University Medical Centre Hamburg-Eppendorf and BGI (formerly known as

Beijing Institute of Genomics) to complete the sequence. The research groups used

Life Technologies’ Ion

Personal Genome Machine (PGM). Simultaneously,

University Hospital of Muenster in Germany and Life Technologies confirmed these results.

Information Uncovered by Sequencing

“Bioinformatics analysis revealed that this

E. coli is a new strain of bacteria that is highly infectious and toxic,” BGI said in its report, issued on June 2. The bacterium is an enterohemorrhagic

E. coli (

EHEC) serotype O104 strain, which has never been involved in any

E. coli outbreaks before, the institute explained.

Described as super-toxic, the strain has 93% sequence similarity with the enteroaggregative

E. coli (

EAEC) 55989 strain isolated in the Central African Republic and known for causing serious diarrhea. Furthermore, the scientists reported, it has “acquired specific sequences that appear to be similar to those involved in the pathogenicity of hemorrhagic colitis and hemolytic-uremic syndrome.”

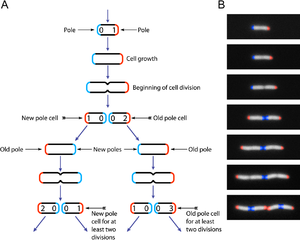

Image via Wikipedia

Image via Wikipedia

The bacteria also produce extended-spectrum beta-lactamases, enzymes that confer resistance to most beta-lactam antibiotics including penicillins, cephalosporins, and the monobactam aztreonam.

University Hospital of Muenster and Life Technologies further noted that “the bacterium at the root of the deadly outbreak in Germany is a new hybrid type of pathogenic

E. coli strain.” Their data reportedly showed the presence of genes typically found in two different types of

E. coli: EAEC and EHEC.

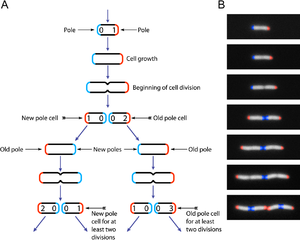

The Instrument that Did the Sequencing

The Ion PGM chip-based sequencing technology connects chemical and digital information through the use of semiconductor technology. It uses a parallel array of semiconductor sensors to perform real-time measurement of the hydrogen ions produced during DNA replication.

A high-density array of wells on the ion semiconductor chips provides millions of individual reactors, while integrated fluidics allows reagents to flow over the sensor array. The combination, Life Technologies says, enables the direct translation of genetic information to digital information.

Image via Wikipedia

Image via Wikipedia

“What’s different about it is that it doesn’t use cameras or lasers,” Life Technologies CEO Mark Stevenson told GEN. “We measure the pH change in each well with a semiconductor chip.”

The

E. coli crisis in Germany appears to have provided the proof of principle and a field test with highly visible results for the Ion PGM. Life Technologies acquired the technology when it bought

Ion Torrent in 2010 for $375 million in cash and stock. Life Technologies began selling the instrument to the marketplace for less than $100,000, calling it an “easy-to-use, highly accurate benchtop instrument optimal for mid-scale sequencing projects such as targeted and microbial sequencing.”

When Ion Torrent introduced the technology in 2007, it expected the innovation to democratize research, enabling every lab to have a sequencer on its bench. At the time, the company said it had planned to sell the machine for $50,000 apiece—about one-tenth the cost of existing instruments. Ion said that the instrument could perform a single sequencing “run” for about $500 in one hour.

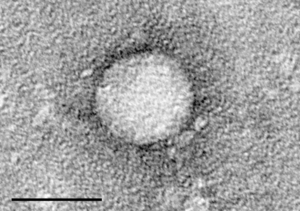

Detection in Food

The availability of new technologies has indeed greatly facilitated the genomic sequencing of this potentially lethal bacterium. Life Technologies has also developed a tool to test foods thought to be associated with the outbreak.

On June 6, shortly after reporting results from its sequencing efforts, the firm reported that it had completed development of a custom assay to detect the bacterium. Shipments of the

TaqMan®

E. coli O104 detection kit are now in Europe.

“A

qPCR-based assay test is the most accurate method to detect harmful food-borne pathogens because a positive result indicates the presence of that particular strain’s DNA in the food sample that is being tested,” explained Nir Nimrodi, head of food safety at Life Technologies.

Image via Wikipedia

Image via Wikipedia

“It is also the fastest. While traditional laboratory testing methods can take up to 10 days for results, this test can determine the presence or absence of the European pathogen in 10 to 24 hours, depending on the sample type and size.”

It is hoped that the TaqMan

E. coli O104 detection kits will provide an answer to the question that has received a variety of answers since the initial

E. coli outbreak: Where did it come from? Originally, on May 26, health officials pointed to

E. coli-contaminated cucumbers from Spain as culprits, but researchers later concluded that the cucumbers were contaminated with a different strain.

Suspicion then moved to bean sprouts but faded away after it was found that 23 of 40 samples from the suspect farm tested negative. As of June 8, focus had shifted back to cucumbers, as a CUCO (cucumber of unknown country origin) that had sickened a family in eastern Germany was found to be contaminated with the outbreak strain. The cucumber was discovered in the family’s compost, but there is no conclusive evidence that it’s the source.

Then on June 10, Reinhard Burger, president of the

Robert Koch Institute, said that even though no tests of the sprouts from the suspect farm had come back positive for the

E. coli strain behind the outbreak, an investigation into the pattern of the outbreak had produced enough evidence to indict the sprouts. German authorities said that they haven’t yet been able to resolve how sprouts at a farm became contaminated.

Along the search for clues about the source of the killer

E. coli food bug, a restaurant in the northern German town of Luebeck and a festival in the northern city of Hamburg have also come under suspicion. The European Union has sent food safety experts to Germany to help authorities there identify the source of the deadly

E. coli epidemic.

Stevenson noted that “a concern for the global healthcare industry is the ability to identify these pathogens as they arise and then be able to detect and screen for them rapidly and inexpensively.” Like with the Ion PGM, as novel pathogens continue to emerge, so will the need for similar disruptive but relatively affordable technologies.

Image via Wikipedia

Image via Wikipedia

Image via WikipediaJ. Craig Venter: Designing Life

Image via WikipediaJ. Craig Venter: Designing Life